The woman who wrote a law banning discrimination based on natural hairstyles, adopted in 19 states, will be coming to Arlington to talk about anti-Black bias in the legal profession.

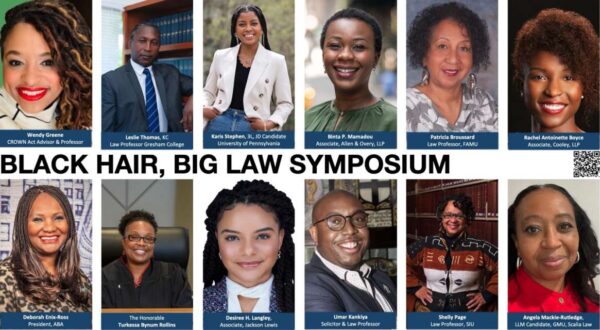

Wendy Greene, architect and advisor on the “Creating a Respectful and Open World for Natural Hair Act of 2022” (CROWN Act), will be joined by other lawyers and legal scholars at George Mason University’s Antonin Scalia Law School tomorrow (Thursday) to tackle whether the jobs in the nation’s top law firms, known as “big law,” are less attainable for Black people who wear their hair in afros, dreads or braids.

The two-hour “Black Hair, Big Law” symposium sponsored by George Mason’s Black Law Student Association will feature talks by American Bar Association President Deborah Enix-Ross and other lawyers and scholars from across the U.S. and the Atlantic Ocean. Attendees can RSVP online and attend in-person at the law school (3301 Fairfax Drive) or via Zoom.

The symposium kicks off at 11 a.m., with lunch starting at noon for in-person attendees. Per a press release, it will include:

- A distinguished panel of knowledgeable, relatable, and trailblazing speakers

- Compelling original quantitative graduate research black attorneys and their hair

- Poignant, thought-provoking videos about attorneys and judges wearing their hair natural

- Representation matters: 100 Black TV and Film Lawyers from the controversial “Amos & Andy” to the new CBS legal drama, “All Rise.”

All attendees will receive an anthology of nearly 100 first-hand experiences from Black attorneys, paralegals and law students describing discrimination they faced, or expected to face, because of their hair.

Here are some anecdotes:

“Depending on the court, I [used] to change my hair,” says one woman, per the press release. “As a black woman in many jurisdictions, the court assumes I am either a party to the case or the court reporter. So I would style my hair differently and in fact, dress differently to set myself apart or rather to attempt to set myself apart.”

“”I was told to change my hair when I entered law school. In law school, when in mock trial competitions my hair was judged and questioned by my coaches. Despite it all, I am who I am. My hair is a part of who I am. Thankful for my Howard University experience that helped solidify that being Black is not a badge of shame. Neither is my hair.”

Black people have long been discriminated against for wearing afros, braids or dreads, event organizers say. Some student dress codes forbade them, some people have been fired for wearing dreadlocks and women who wear their hair curly have been stigmatized as choosing a less professional style.

In the face of discrimination, Black men could choose to wear their short, but for many women, their choice is between keeping it natural or straightening it with chemicals.

This alternative, popular for decades — despite the uncomfortable side effects, such as sores — has recently been linked to uterine cancer. It prompted lawsuits to be filed in California, Illinois and New York, according to the online law blog Above the Law.

The murder of George Floyd by Minneapolis police in 2020 prompted a renewed focus on racism, particularly against Black people, within “big law,” where a strong majority of lawyers are white, the American Lawyer reports.

The law publication’s annual “Diversity Scorecard” for 2022 showed the greatest annual increase in the percentage of minority attorneys in the industry since 2001.

The total number of minority attorneys rose to 20.2%, up from 18.5% last year and 17.8% in 2020. The number of minority partners also climbed, reaching 11.9%, up from 10.9% in 2021, and the percentage of minority nonpartners hit 26.7%, up from 24.6% in 2021.

Meanwhile, another law publication, JD Supra, reports that 18% of all attorneys in the nation’s 200 largest law firms, ranked by revenue, are “ethnically diverse” — up a percentage point from 17%, where it sat from 2019-21.

Despite the recent progress, advocates say new lawyers will not stay if big law does not address systemic issues, such as when firms protect powerful partners accused of bullying, harassment or racial bias.