Lyon’s Legacy is a limited-run opinion column on the history of housing in Arlington. The views expressed are solely the author’s.

Lyon’s Legacy was a series that ran for the last four months on ARLnow, telling a story of the history of housing and racism in Arlington, and putting forward a suggestion for one way we could end the regime of economic exclusion that has dominated most of our county for the last century. As the series ran, some eagle-eyed readers kindly identified a few mistakes in the historical research.

In this follow-up article, I’ll address and hopefully correct those errors. You can read the whole essay, with these corrections incorporated, here.

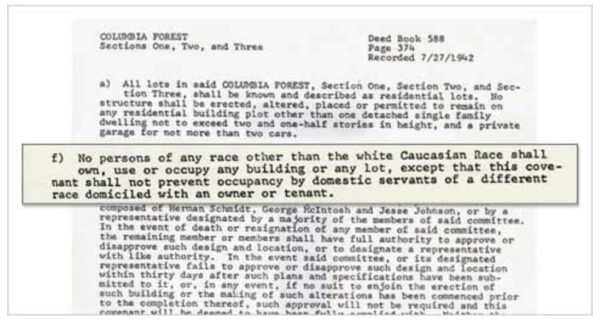

All of these errors are significant, in the sense that any factual error in a piece of historical writing is significant. But correcting these errors does not change Arlington’s history of racial exclusion through single-family zoning and does not change our responsibility to end this exclusion by legalizing multifamily housing county-wide.

I offer my apologies to readers for my failures in research and my gratitude for those who helpfully corrected my mistakes.

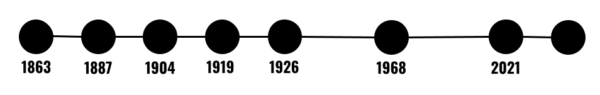

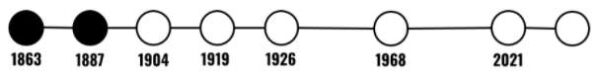

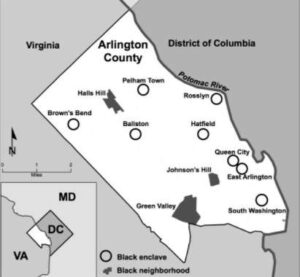

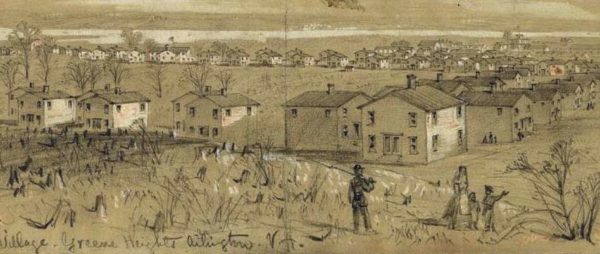

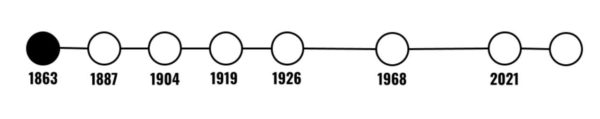

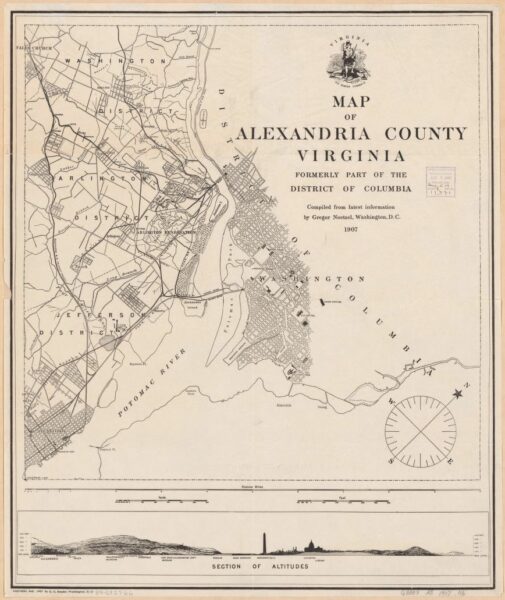

1. My description of Freedman’s Village failed to mention that residents were subject to labor requirements — a major omission. Nonetheless the Village was a better place for Black people to live in the 1870s than most of the rest of the South, as proven by their commitment to staying there until they were evicted in the winter of 1887. An imperfect attempt at racial inclusion would still make a fine symbol for our county.

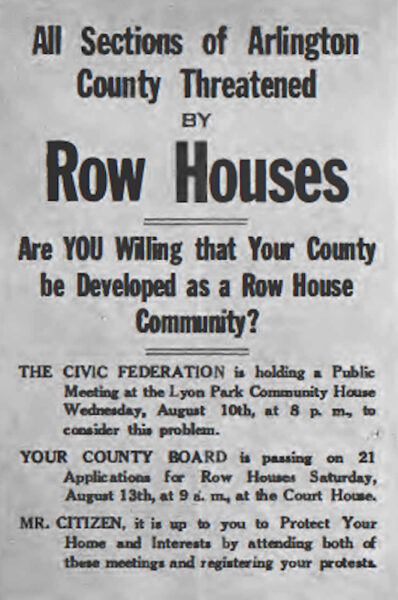

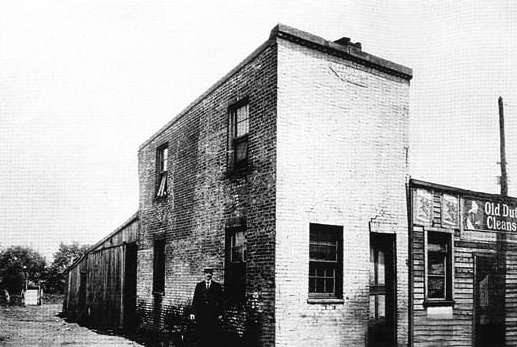

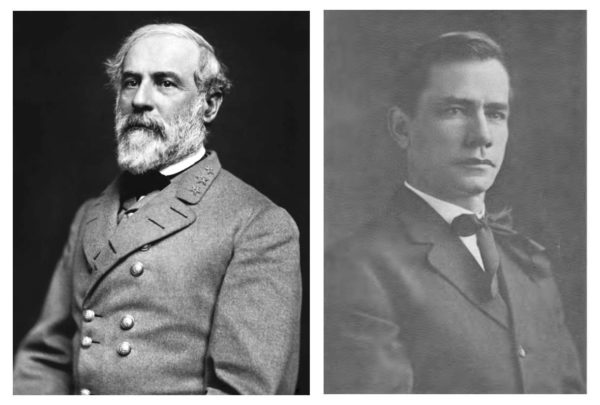

2. Crandal Mackey’s raid on Rosslyn was not solely motivated by white supremacy. I failed to mention that one of the primary victims of the raid, Eddie Heath, was white; I underemphasized the extent to which violent and non-violent crimes did indeed take place in Rosslyn; and for the sake of the narrative I didn’t mention the same-day raid in Jackson City (another relatively unsegregated community).

Mackey was also a prohibitionist, and it may well be that he saw alcohol, rather than Black people, as the more significant barrier to Arlington’s development. But prohibition and racism were closely intertwined, and it’s worth remembering that drugs are still used as an excuse for selective enforcement and police brutality today.

3. Arlington did not institute segregation districts in 1912. Virginia passed a law in 1912 permitting localities to institute such districts, and five years later the law was deemed unconstitutional. During that five years, Arlington did not take advantage of its power to segregate. This detail is pretty much irrelevant to the history of segregation after 1917.

4. When touching on the history of economic racism in America, I referenced median household wealth. This can be a misleading indicator because it doesn’t account for variation in age, family size, etc. But my argument wasn’t meant to be nuanced — I was only trying to show that there exists a large historical racial wealth gap in our country. This inequity is real, and it can be illustrated by any number of more nuanced indicators.

No matter how it’s measured, the racial wealth gap has a major bearing on people’s ability to buy single-family homes in Arlington.

5. I failed to tell the stories of other racial and ethnic groups besides Black and white Arlingtonians. A major portion of our county today is Hispanic or Latino, and we boast sizable populations from countries all around the world. Those are fascinating, important stories, and they deserve to be told well in their own articles.