Making Room is a biweekly opinion column. The views expressed are solely the author’s.

The following was written by guest columnist Kaydee Myers.

Over the next two years, the Arlington County Board and the Arlington School Board have the opportunity to create a more integrated community through four concurrent planning efforts.

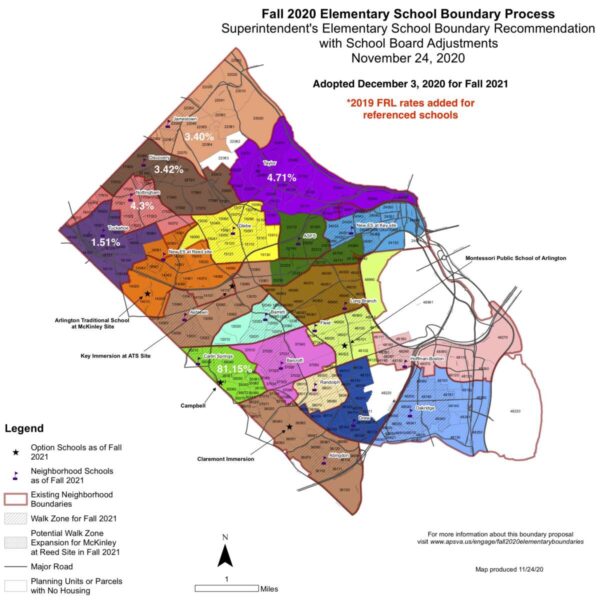

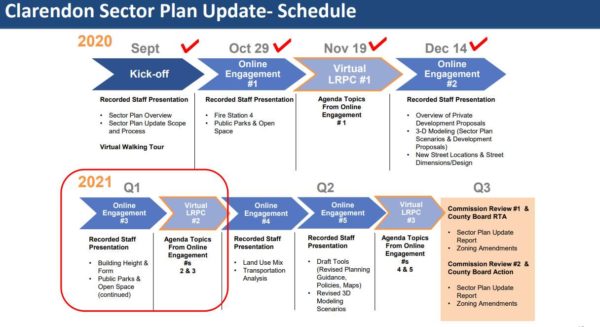

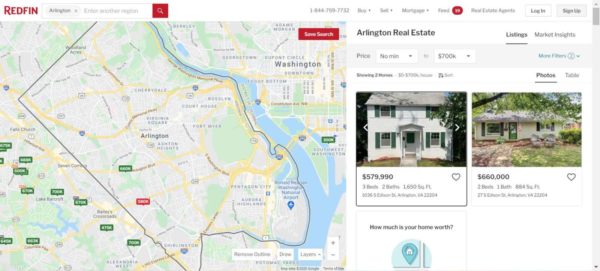

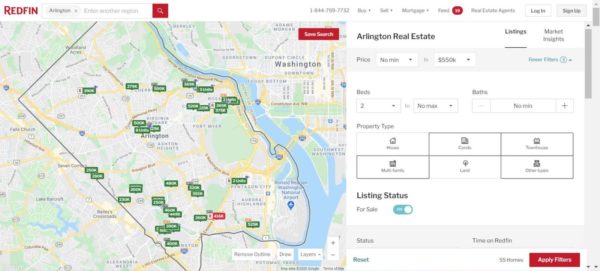

Arlington County started its Missing Middle Housing Study and Affordable Housing Master Plan Review, while also drafting a plan for (the soon to-be-renamed) Lee Highway. Meanwhile, the School Board will adopt comprehensive elementary school boundaries in Fall 2022.

If the Boards coordinate these efforts, they could institute multi-family zoning in a portion of the area assigned to each neighborhood elementary school, leading to more mixed-income housing in neighborhoods currently lacking these options.

As in most public school districts in the nation, Arlington operates neighborhood schools, where most kids go to school based on where they live. Similarly, like most urban areas, Arlington County housing patterns reflect ingrained racial, ethnic, and economic segregation after years of discriminatory government policies and coordinated racist real estate practices. Our schools reflect this housing framework.

Past efforts, such as busing for integration, have fallen out of favor with parents, elected officials, and the courts. Other efforts, like option schools, are models for integration, but are not widespread enough to change the system. Plus, APS reports that Arlington parents voice a strong preference for walkable neighborhood elementary schools, and there are valid economic, environmental, and health benefits for promoting this walkability.

With this backdrop, APS is unlikely to challenge the status quo. However, APS can increase integration with intensive joint planning with the County Board to address school segregation where it starts — its neighborhoods. Many community members, including School Board member Reid Goldstein have called for this joint planning. But, despite being one of the 10 people in the County able to implement this collaboration, Mr. Goldstein didn’t elaborate on how to get started.

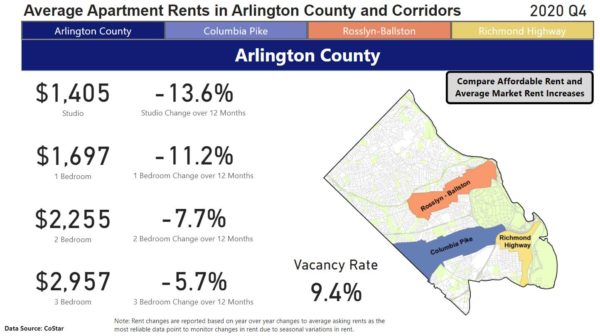

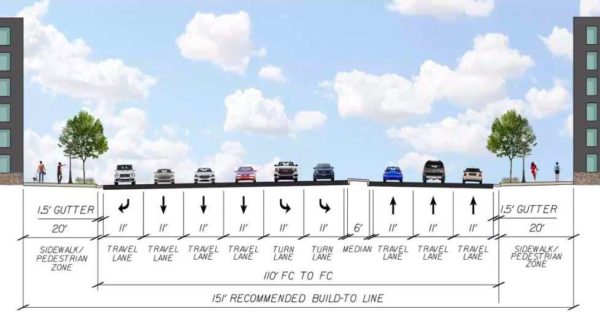

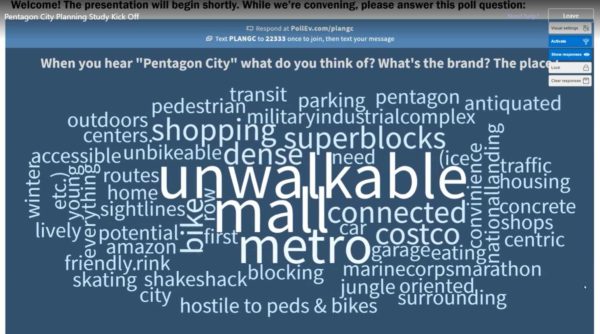

The most promising opportunity to improve integration within APS is the County’s Plan Lee Highway initiative. By reimagining Lee Highway as a walkable urban boulevard, a rezoning effort could add mixed-income housing in the northernmost quarter of Arlington — neighborhoods with the highest median incomes, which flow to elementary schools with the lowest poverty rates in the County.