The next year will see some important steps forward as Arlington County looks to uncouple law enforcement from its response to homelessness and behavioral health crises.

In 2024, the county will implement new protocols and a call system to ensure people experiencing behavioral health crises — due to a mental illness, substance use disorder or disability — receive services rather than get arrested and jailed.

The coordinator of the forthcoming Marcus Alert system, Tiffany Jones, provided the update during an Arlington Committee of 100 forum last week, adding that more details will emerge during the implementation stage.

“The main purpose is to ensure that everyone has equal opportunity, accessibility to services and is treated with dignity and respect and given the proper services that they need to thrive,” Jones said. “However, there is a specific mission to increase the availability of and access to racially responsive crisis supports — so, in short, to target the BIPOC [Black, Indigenous, People of Color] community.”

The system comes from the Marcus-David Peters Act, which was signed into law in late 2020 and is named for Marcus-David Peters, a Black, 24-year-old biology teacher who was killed by a police officer in 2018 in Richmond while experiencing a mental health crisis.

Once operational, the system will transfer people who call 911 or 988, the national suicide and mental health crisis hotline, to a regional call center. There, staff determine whether to de-escalate the situation over the phone, dispatch a mobile crisis unit or send specially trained law enforcement.

“Our emergency communications center partners have been doing a wonderful job in getting trained on mental health, psychotic disorders, substance use, suicide prevention, trauma-informed care: various different topics that will help them learn how to assess and manage and transfer calls when they receive Marcus Alert-type calls,” Jones said.

The regional crisis call center is also building mobile crisis teams, Jones said, noting more information on these teams will come out at the time of implementation in December.

“Arlington County and the police department are well ahead of what the state protocols are for the Marcus Alert implementation that we’re working towards in 2024,” ACPD Community Engagement Division Supervisor Lt. Steve Proud said.

The state required localities to ready implementation plans by the summer of 2022. However, localities have until 2028 to stand up a Marcus Alert system.

So far, five localities within each region of the state have operating programs, according to the Virginia Dept. of Behavioral Health and Development Services:

- Western: Madison and Fauquier counties, plus Warrenton and Culpeper

- Northern: Prince William County

- Southwest: Bristol and Washington County

- Central: Richmond

- Southeast: Virginia Beach

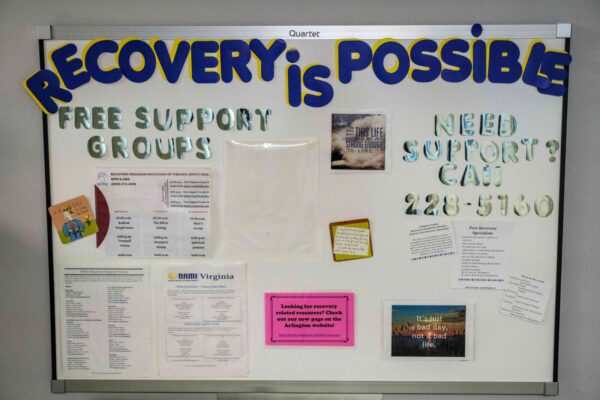

Jones had another big announcement last week related to the county’s “Mobile Outreach Support Team.”

“When we implement the funding that we will get from the state [for Marcus Alert], we’re going to expand our MOST team due to how effective they have been in the community and pouring into our community members,” she said. “So we’ll be able to have new team with a new van, and expanding hours of operation as well.”

MOST launched this summer and comprises licensed clinician, a peer recovery specialist and an outreach worker from the Dept. of Human Services. Between 1-9 p.m., they respond to referral calls in a retrofitted van equipped with everything from a defibrillator to Narcan and fentanyl test strips.

The vehicle was funded through a 2-year, $390,000 federal grant.

MOST Coordinator Michael Keen said he conducts homeless outreach while shelters, the public and the police department refer individuals to him, so he can introduce them to county programs. He says he has received 45-55 referrals per month in the last two months, up from an average of 15-20, largely from police.