Amazon executives say they’re looking forward to becoming “good neighbors” in Arlington, delivering a decidedly optimistic message to local leaders in one of the company’s first public events since tabbing the county for its new headquarters.

The tech giant’s head of worldwide economic development, Holly Sullivan, assured a crowd of government officials and business executives last night (Thursday) that the company is looking to build a “sustainable long-term partnership” in the region. That presented a stark contrast with Amazon’s recent decision to spurn New York City over concerns that local leaders were insufficiently supportive of a new headquarters there.

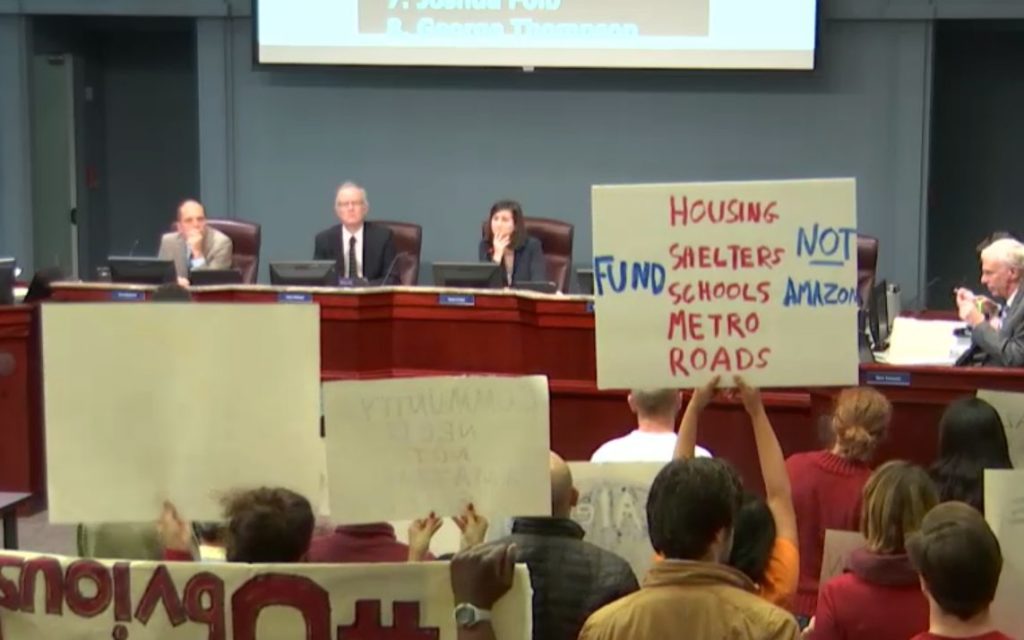

The event, organized by the Metropolitan Washington Council of Governments and held at George Mason University’s Virginia Square campus, also came just a few days after Arlington officials and activists expressed concern that Amazon executives haven’t done enough to engage the community as it gears up to move into the area.

Sullivan challenged that idea Thursday, arguing the company plans to be “active in the community” and has “just started our outreach” in Arlington. But only a limited group of Arlingtonians had the chance to hear that message — the event was “invitation-only,” though the COG did offer a livestream for anyone hoping to watch from home.

That stricture prompted some local critics of the project to refuse to attend the event, calling on the company to hold public hearings with community members instead. Many have been especially critical of Arlington’s proposed incentive package for Amazon — if the County Board approves it next month, Arlington would fork over $23 million over the next 15 years to a company owned by the world’s richest man.

On that front, Sullivan was able to offer significantly less reassurance. In response to a rare question from a reporter at the event, she pointedly would not say whether the company would pull the plug on its Arlington plans if the Board rejects the incentive package.

“The talent in the area was the primary driver of this entire process,” Sullivan said. “But incentives are important to us. They give us an opportunity to reinvest in our infrastructure and development opportunities for our workforce.”

Of course, it’s quite unlikely that the Board would take such a step. Even Board members who have expressed some unease with the incentive package have reasoned that it’s a small price to pay for the 25,000 (or more) jobs Amazon hopes to bring to the county.

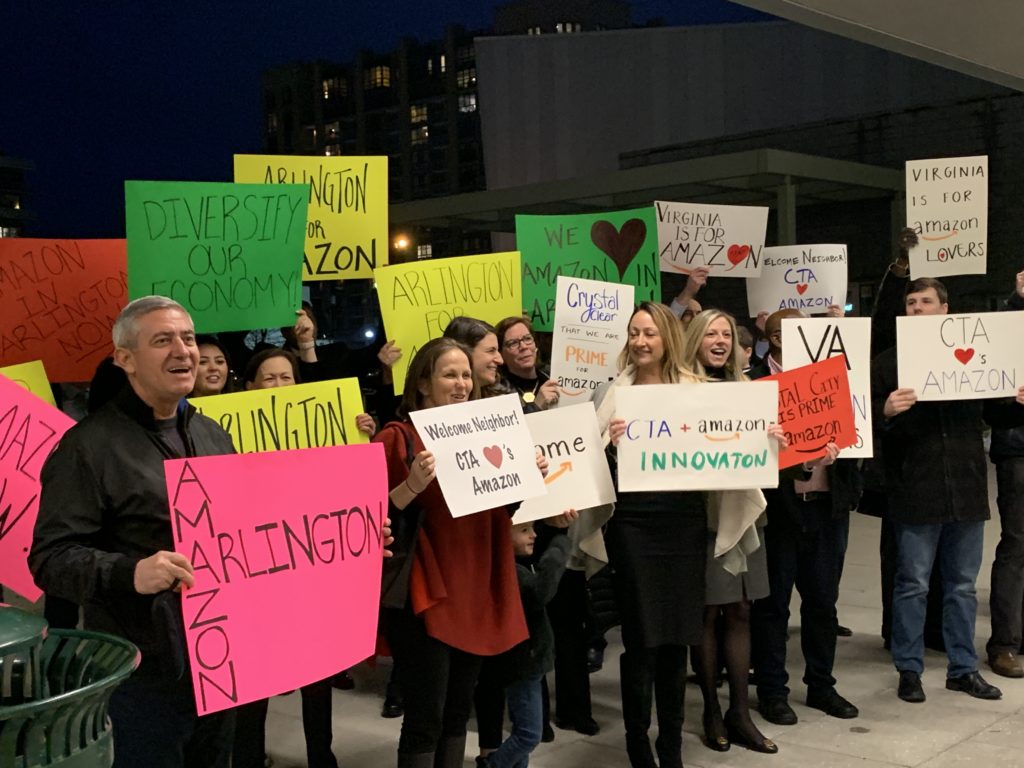

The business community has also been increasingly vocal in support of the project. Not only has the Arlington Chamber of Commerce repeatedly thrown its weight behind the effort, but the Crystal City-based Consumer Technology Association recently joined in the fight as well. The CEO of the tech advocacy group attended the event to welcome Amazon to the neighborhood, and the CTA organized a crowd of dozens of pro-Amazon demonstrators to hold signs outside the gathering.

“We know this is a historic moment, not just for Arlington, but the whole region,” said Victor Hoskins, head of Arlington Economic Development.

To assuage anyone concerned that the company would bring a huge surge of out-of-state workers to jam area roads and pack local apartment buildings, Sullivan stressed that, in a perfect world, company executives “hope to hire all 25,000 workers locally.”

But she followed that up with a laugh, acknowledging that such a possibility is a bit unlikely. However, she is confident that D.C. region has enough highly skilled tech workers to provide a deep hiring pool for Amazon. And it helps, she believes, that the company already has corporate offices in both Herndon and D.C. to draw from too.

“A few people may choose to relocate from our Seattle headquarters, but this is not a relocation of corporate employees from Seattle,” Sullivan said.

Sullivan added that, wherever the company’s employees hail from, Amazon plans to design its offices in a way to “push employees out into the neighborhood to support local businesses.”

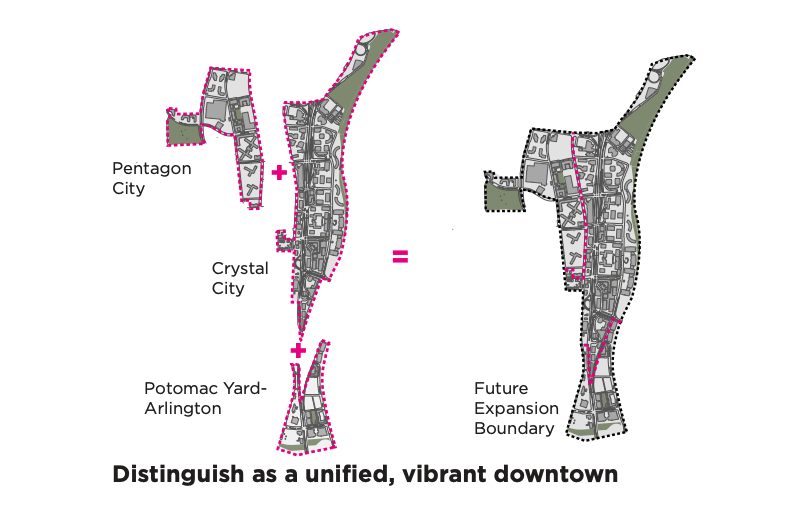

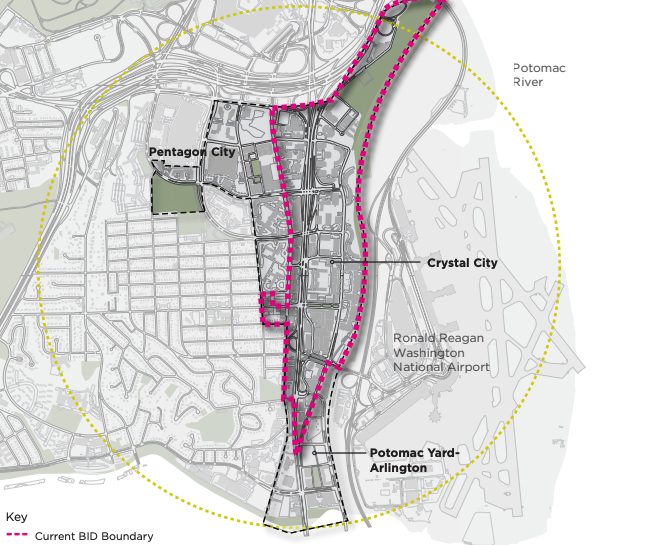

While the tech giant is still in the most preliminary phases of designing the office space it plans to lease from JBG Smith in Crystal City and build in Pentagon City, she said the company fully expects to draw from the design principles it used in Seattle.

“We’ll be trying to take the indoors outdoors and vice versa,” Sullivan said. “We want it to feel very much like a neighborhood. There will be no walls around it, no big sign that says ‘Amazon’ on it.”

That includes a focus on welcoming retailers and other restaurants onto the ground floor of the company’s offices. Though JBG has already worked fervently to bring more mixed-use developments to the area, it’s a process the area’s dominant property owner is hoping that Amazon will accelerate, to the whole neighborhood’s benefit.

“Crystal City gets pretty quiet at night, because everyone leaves right after work,” said Andrew VanHorn, JBG Smith’s executive vice president. “It may not be 24/7, but we want to make it more of an 18/7 environment.”

Until the Board signs off on the incentive package and Amazon starts submitting construction plans for its new offices, VanHorn pointed out that any design conversations are quite preliminary at this point.

However, he said JBG is working under the general assumption that the company will move into all of its leased office space in Crystal City by 2020. Then development work on a new building at Metropolitan Park in Pentagon City will run roughly from 2021 to 2025; construction at the former “Pen Place” development will run from 2023 to 2027.

Sullivan stressed that the buildings won’t look too out of step with the existing skyline, saying executives hope to “integrate into what’s already there” in Pentagon City.

Arlington’s notoriously extensive civic engagement process for new developments offers a long road ahead for the company, but Sullivan said she’s looking forward to embarking on it to answer a simple question: “How can we be a better neighbor?”

“We’re all doing this together,” Sullivan said. “We’re going to be neighbors.”