On Election Day, a majority of Arlingtonians approved six bond measures, worth $510 million, that will fund a variety of projects throughout the county.

The biggest expenses for the next 10 years include upgrades to its Water Pollution Control Plant, where local sewage goes, and funding to build a new Arlington Career Center campus.

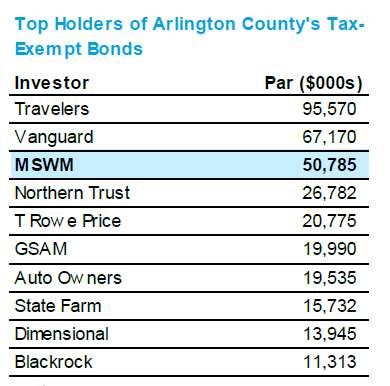

Arlington County finances these big-ticket projects by selling bonds, mostly to institutional investors like Travelers, State Farm and Blackrock, but also — to an extent — to retail investors and residents. It uses bonds, in the aggregate, to pay for smaller-ticket items: new park playground equipment or upgraded HVAC units, lighting and kitchens and new, more secure entrances in Arlington Public Schools.

But earlier this month the bond market took a huge hit, falling more in one day than it had in a decade, the Wall Street Journal reports. Investors had sold off government bonds — normally seen as an “ultrasafe” investment for companies and retirement accounts — in response to higher interest rates, which the Federal Reserve raised to tackle inflation.

That might mean a new type of investor buying Arlington’s bonds.

“With the historically low interest rates over the past decade, smaller retail investors have not been as big a presence, however with recent rate increases their participation may increase,” county spokesman Ryan Hudson said.

But for Chris Edwards, a researcher with the libertarian think tank Cato Institute, the current market is more of a reason why wealthy jurisdictions like Arlington should not be using bonds to pay for projects.

“There’s more of an argument for a government to issue debt when interest rates are near zero, which they were a few years ago,” he tells ARLnow. “The era of historically low interest rates for last 10 years is over. It seems we’ll have inflation for a number of years now and that means Arlington’s borrowing costs are going to be higher. It’s the same reason now is not a good time to buy a house with a 30-year mortgage.”

For the county, bonds are a “generational equity issue,” Hudson said.

“The use of municipal bonds spreads payments over ten or twenty years, which more closely aligns with the useful life of County projects and requires future residents to bear some of the burden of paying for the costs of projects from which they directly benefit,” Hudson said.

In other words, it wouldn’t be fair or financially feasible for current residents to fully fund multi-year capital projects, like the $48 million issued for the Lubber Run Community Center, in one year.

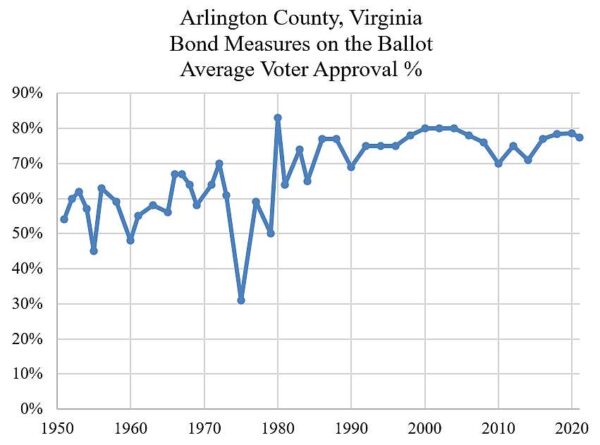

Support for county bond referenda has plateaued since the 1980s, after climbing from an average passage rate of 58% from 1951 to 1979 to an average rate of 75% from 1980 to 2021, Edwards wrote in a blog post discussing bond passage margins in Arlington since the 1950s.

While the 2022 bond referenda all passed, registered voters were marginally more supportive of wastewater plant updates (85% approval) and stormwater improvements (80% approval) — perhaps in response to recent flooding events — than they were for renovations to county buildings (72%), parks (79%) and schools (77%), according to results from the Virginia Dept. of Elections.

Although three-quarters of Arlington residents generally vote for bonds, there is some criticism about the method for funding projects as well as to the kind of projects it is applied.

“I think, especially a place like Arlington, I don’t see an advantage in using debt,” Edwards tells ARLnow. “If the County Board thinks it needs a new library or high school, they should make the case to raise property taxes to fund the things they want. In my view, that would be more transparent.”

Voters tend to reject tax increases but they tend to support bonds, he said. That dissonance, he concludes, is the result of “a case of misinformation.”

“Bonds increase taxes in the future because the government is going to have to pay the interest on those bonds,” he said. “Who are we, today, to impose interest costs on Arlingtonians 10-20 years down the road?”

He said he is not against debt for big projects with long-lasting benefits, such as D.C.’s bonds to fund sewage improvements. But smaller things, like school improvement projects, should not be bond-funded.

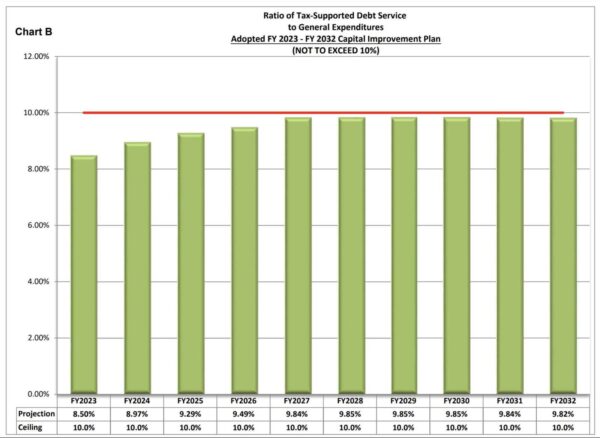

There is also concern from some that the county is close to maxing out some of the limits that it self-imposes in order to regulate how many bonds it issues. These limits exist to ensure Arlington maintains its triple-A bond rating, given by credit agencies that have determined the county has an excellent track record of paying back its debts.

The county tries to keep how much debt is paying off to 10% of its general expenditures. Over the next 10 years, the ratio is expected to peak at 9.85%.

Another ratio that the county is close to maxing out is the ratio of debt per person to income per person, which cannot exceed 6% and over the next 10 years could range from 4.5-5.9%.

It is possible for the county to max out on how many bonds it can issue, Hudson said. But when asked if Arlington County could still issue bonds in the next 10 years, Hudson said “the short answer is yes.”