This sponsored column is by James Montana, Esq., Doran Shemin, Esq. and Laura Lorenzo, Esq., practicing attorneys at Steelyard LLC, an immigration-focused law firm located in Arlington, Virginia. The legal information given here is general in nature. If you want legal advice, contact James for an appointment.

It’s election time again in Virginia! We are currently in the middle of early voting for Governor, Lieutenant Governor and various other positions within the Commonwealth’s government.

Now is a good time to provide you — our readers — with information on how elected officials, in particular at the state level, interact with immigrants who are victims of crime. Here at Statutes of Liberty, we don’t make political endorsements or take policy positions. We’re here to tell you about the U Visa — one of the most important ways that state government and immigrant communities interact.

First, some background. Congress created the U visa as part of the Victims of Trafficking and Violence Protection Act (2000). The U Visa itself benefits victims of certain qualifying crimes who assist in the investigation and prosecution of those crimes. Qualifying crimes include, among others, stalking, false imprisonment, felonious assault and domestic violence.

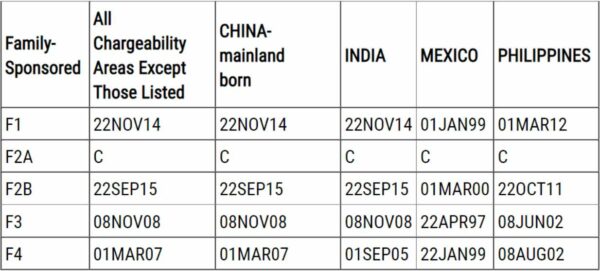

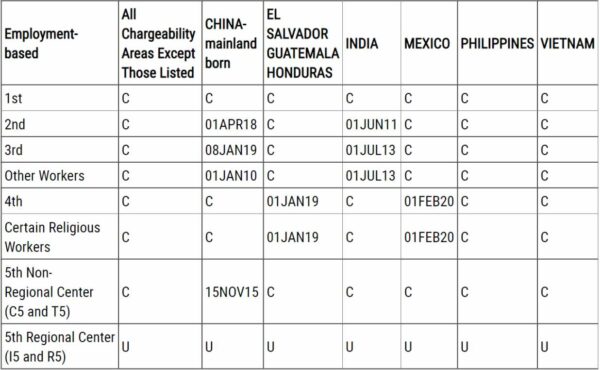

Congress intended, by creating the U Visa, to provide an incentive for undocumented immigrants to cooperate with the police, but the allowable relief is fairly limited in scope. Congress allocated only 10,000 U visas per fiscal year, meaning only 10,000 applicants may receive that visa each year. If an immigrant receives a U visa, it is valid for three years. After those three years, the immigrant may apply for a green card.

As part of the U visa process, the applicant must receive certification from a certifying official, affirming that the applicant was and continues to be helpful to law enforcement. Most police departments and prosecutor’s offices have certifying officials to review certification requests from applicants.

Unfortunately, it is not uncommon to wait many, many, months for the certifying official to make a decision about whether to certify the applicant’s request. Furthermore, the method of obtaining certification in a given jurisdiction is sometimes unclear. The Virginia legislature sought to fix this problem earlier this year.

On March 31, 2021, Governor Northam signed SB 1468 into law. The law went into effect on July 1, 2021. The law seeks to clarify and rein in the certification process. Now, law enforcement agencies are required to respond to certification requests in writing, either by certifying the request or providing the reasons the law enforcement agency will not certify.

Importantly, the law also created deadlines for a response to a certification request. Under normal circumstances, certifiers now have a 120-day deadline to issue a decision. For immigrants in deportation proceedings, law enforcement agencies must complete the certification within 21 business days.

If the principal applicant has children who will “age out” (turn 21 and no longer qualify to be a derivative on their parent’s application) without expedited processing, the certifier must make a decision within 30 days.

Finally, another important piece of the law allows for applicants to petition a Circuit Court to review the determination if the certifier does not make a decision within the statutory time frame or refuses to provide certification. This new law helps clarify the U visa process for applicants and also holds law enforcement agencies accountable, which further supports the policies regarding victim assistance and protecting public welfare.

The federal government also began a new program to assist immigrants seeking U visas. As previously mentioned, there are only 10,000 visas available per year. However, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) receives tens of thousands of applications each year. Therefore, there is a tremendous backlog of these cases, with many applicants waiting anywhere from five to seven years for a decision in their case.