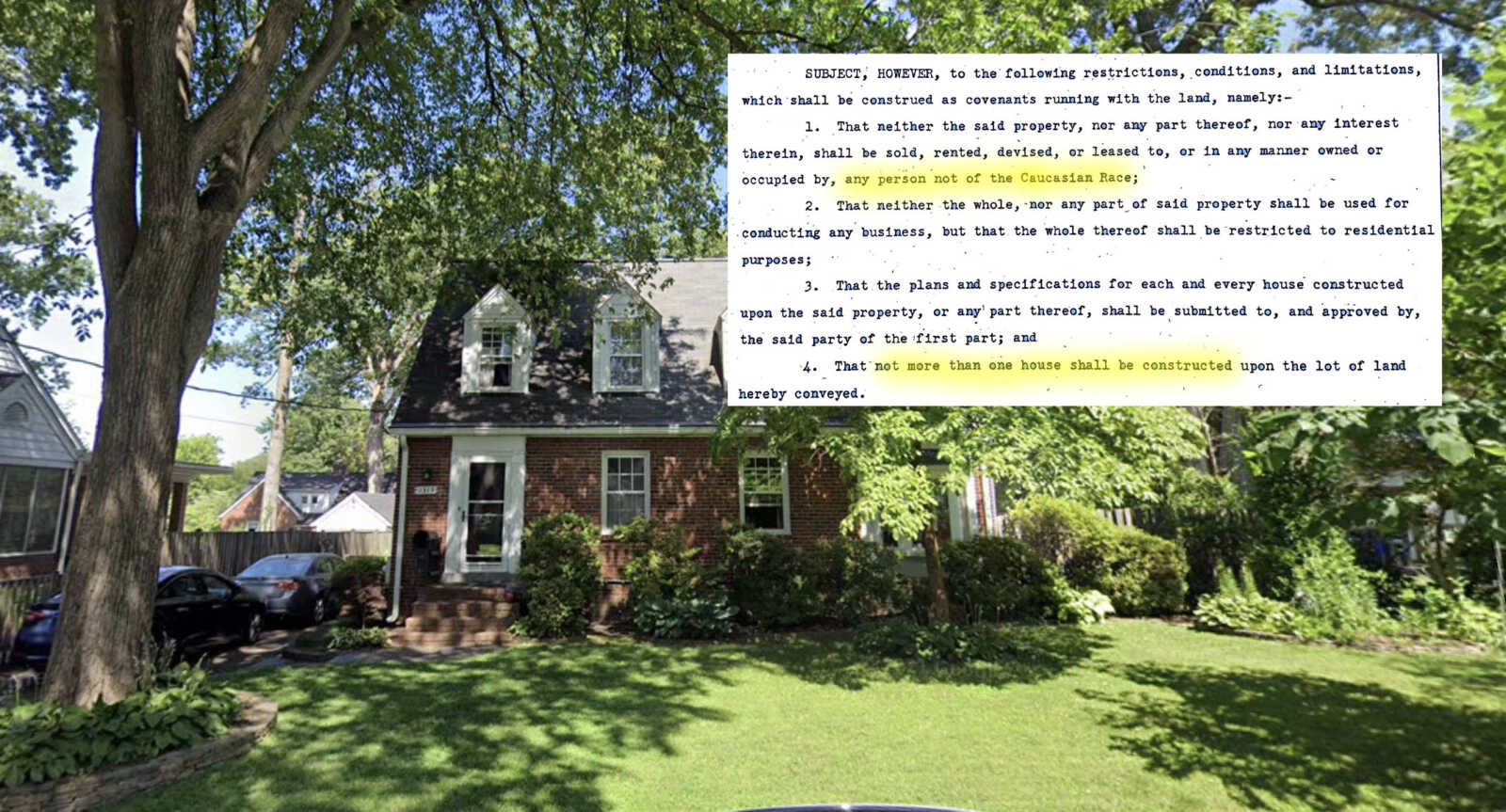

Using a restrictive covenant in a 1938 deed, neighbors in the Tara-Leeway Heights neighborhood convinced a developer to build a single-family home instead of a duplex.

The home, 1313 N. Harrison Street, is not far from a wall that separated the historically Black neighborhood of Hall’s Hill from single-family-home subdivisions originally built exclusively for white people. In addition to specifying that only one home can be built on the lot, a second provision in the deed bars owners from selling to people who are not white.

This second provision came to light this week after ARLnow and Patch reported on the neighbors convincing the developer to back down from building a two-family home. A copy of the deed circulated on social media shortly after and ARLnow obtained a copy from Arlington County Land Records Division to confirm its authenticity.

While racially restrictive covenants were rendered unenforceable by a 1948 U.S. Supreme Court ruling and illegal by the Fair Housing Act of 1968, many homeowners never scrubbed them from their deeds, according to local researchers who are mapping racially restrictive covenants in Arlington. Thus, in some cases, they exist alongside separate covenants restricting multifamily construction.

Using the covenant against multifamily housing appears to be a valid workaround for neighbors and Arlington County says it has no legal role in how these covenants are used between private parties. The county began approving 2-6 unit homes in previously single-family-only neighborhoods two months ago, but this is the first instance ARLnow knows of where such a document was used in this way.

Their use, however, resituates one of the initial reasons Arlington County said it embarked on the housing policy changes in the first place: to right historical wrongs caused by racism. It provoked the ire of some Missing Middle advocates, including the Arlington branch of the NAACP, which is calling on the county to address the issue.

“The whites-only restriction can’t be disentangled from the one-house restriction; they were meant to work together, with the purpose and effect of excluding people of color,” said Wells Harrell, the chair of the housing committee of the NAACP, in a statement. “It is profoundly disappointing to see restrictive covenants from the Jim Crow era being invoked to block new housing and exclude families today.”

Several months ago, Arlington resident Stephanie Derrig identified these covenants as a way property owners could block Missing Middle-type housing from being built in their neighborhood.

She told ARLnow this week that she does not support the racist elements of restrictive covenants. At the same time, she sticks by her belief that a “restricted deed is a land use tool… to protect your largest investment, in many cases.”

YIMBYs of Northern Virginia leader Jane Green and Former Planning Commissioner Daniel Weir, both supportive of Missing Middle, take the view of the local NAACP that the two restrictions are part of one legal document, written with exclusionary intent.

Whether these provisions can be separated is a legal question — and a thorny one, at that, according to Venable land-use attorney Kedrick Whitmore.

When a court rules part of an agreement is unenforceable, the court does not rewrite the agreement to be legal, he said. This principle might affirm the initial view of the developer, BeaconCrest, which argued — before backing down and deciding to build a single-family home — that the document seems unenforceable.

On the other hand, courts do not want to remove other rights and obligations for which two parties negotiated. This means the court could uphold the rest of the agreement, giving credence to the arguments made by the neighbors.

“This is not exactly cut and dry,” Whitmore said. “You could make arguments either way. If you went to court, the stronger argument is for the non-racially restrictive elements to remain valid. But again, that’s a question.”

BeaconCrest could have challenged neighbors by saying these provisions are contrary to public policy, based on the new Missing Middle zoning ordinances, he said.

“My guess is that the developer saw there was going to be a fight of some kind and there was some evidence they could be prevented,” he said. “There’s an argument to be made that they walked away because the lawsuit is not worth it.”

ARLnow asked the county if it considered restrictive covenants as part of its zoning code changes and what, if anything, it can do about them.

“The County is aware of the existence of private covenants on properties in Arlington,” the County Attorney’s Office said in a statement. “However, the County has no legal role in the regulation or enforcement of private covenants, so we cannot comment further on how private individuals might utilize covenants on their property.”

For Derrig, that the county did not build in mechanisms to prevent these types of challenges is proof the changes were done in haste.

“The county either did not do their homework on these tools or they knew about them and thought we as residents were ignorant to them,” she said, calling this loophole “another example of a failed and rushed [Missing Middle housing] zoning change.”

The NAACP also pointed out that the county could have a stronger role.

“Our county leaders face a choice. They can either yield to the demands of those resisting change, or they can adopt progressive policies that allow Arlington to grow responsibly and thrive equitably,” Harrell said.

The NAACP urged leaders to catalogue every deed with restrictive covenants to understand how many properties are affected and where they are located. It also called on them to develop a strategy to prevent these covenants “from frustrating the goal of making housing more attainable, abundant, and equitable in Arlington.”

Two women are already in the process of mapping every racial covenant in Arlington. They declined comment on the covenant that nixed the duplex but said they are still working toward their goal.

Derrig notes that, while some were adopted by white people with racist intent, other covenants exist even in High View Park, another name for the historically Black Hall’s Hill neighborhood.

“[They] use them appropriately as well to protect properties in their families for generations,” she said.

James Jarvis contributed to this report