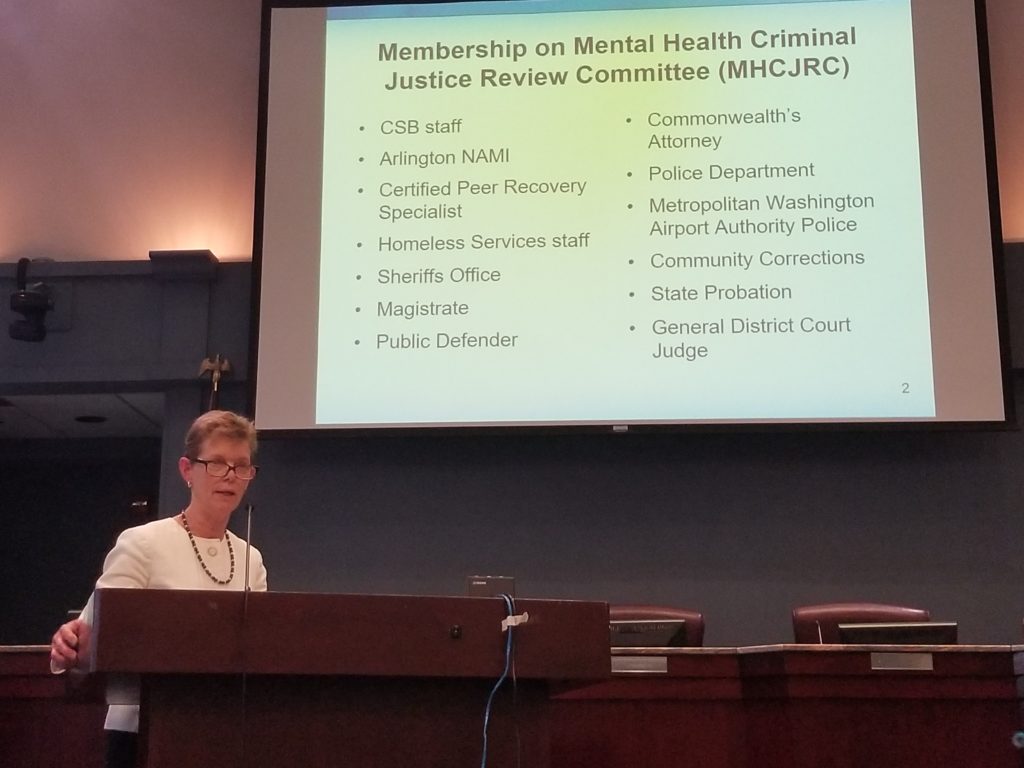

Officials and activists are asking the county courts to make a newly-proposed mental health jail diversion program more inclusive.

Arlington and Fairfax public defenders joined several advocates during a Thursday evening meeting about the proposal, and urged county officials to broaden the mental illnesses diagnoses accepted in the program and not require plea bargains as a participation requirement.

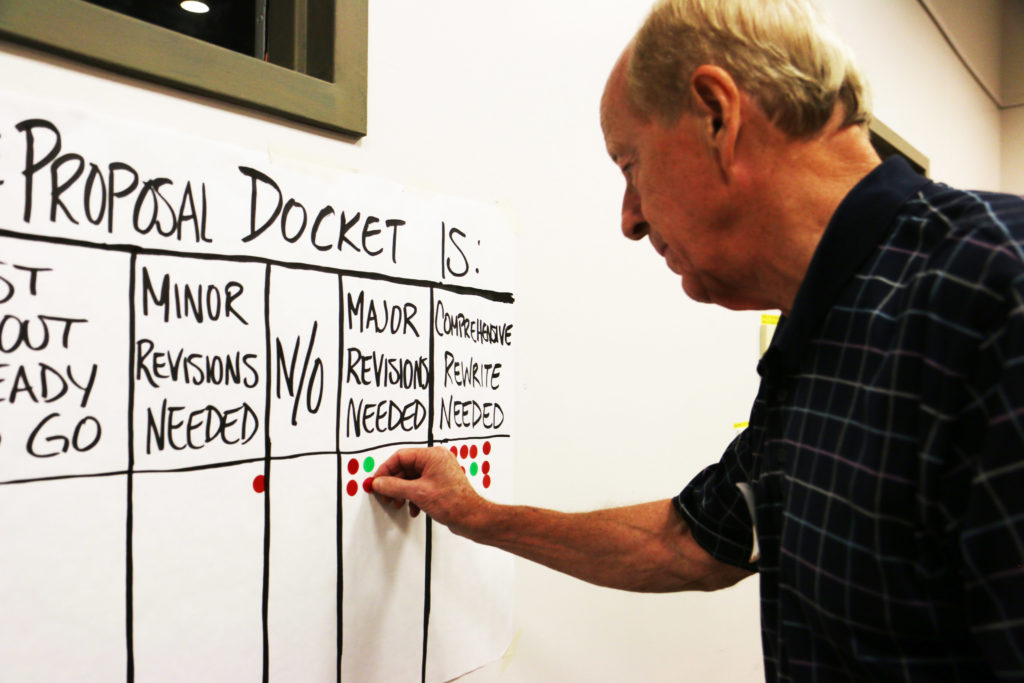

Brad Haywood, who leads the Office of the Public Defender for Arlington County and the City of Falls Church, shared a list of changes his office wants the county to make to the proposal before the county submits the application to the Virginia Supreme Court.

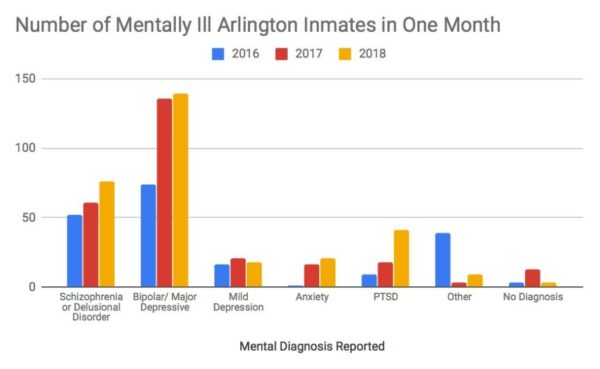

Juliet Hiznay, a special education attorney by training, joined him on Thursday to express concern that only some “serious mental illnesses” were considered shoe-ins for the program, which is called the Behavioral Health Docket.

Hiznay said she was worried that people with developmental disabilities (like ADD or autism) could also benefit from the court-supervised treatment plan, but would be considered “exceptions” under the current eligibility criteria.

Much of the evening focused on discussing whether the county should require participants to plead guilty to their charges before participating in the program (as is currently proposed) or allow them to follow the docket program and then have a trail (as Fairfax County does.)

“Because it requires a guilty plea it literally can’t decriminalize mental illness,” said panelist Lisa Dailey, who analyzes and advises mental illness decriminalization policies at the Treatment Advocacy Center. “So if that’s your goal you’re failing right out of the gate.”

When Arlington Assistant Commonwealth’s Attorney Lisa Tingle asked Fairfax Public Defender Dawn Butorac asks whether the Fairfax docket convicts participants of their charges if they fail out of the program, Butorac said Fairfax prosecutors set no such deals.

“Telling your client ‘if you fail this is what we’re going to do’ is sending the wrong message,” Butorac said.

Haywood pointed out that another benefit of nixing the pre-plea requirement was getting people into treatment fast — something not possible if the county’s tedious discovery process slows down the process.

Haywood also noted that requiring pleas to participate in the mental health service could lead innocent people to say they were guilty in order to access services. He acknowledged that was an “extreme” hypothetical but could be avoided if the county followed Fairfax County’s example of only contending with pleas after a participant finishes their docket treatment plan.

“We are much more inclusive than Arlington,” Butorac said of Fairfax’s docket, which was created after a mentally ill woman was tasered. “When we drafted it, we wanted it to be as inclusive as possible.”