(Updated at 5:35 p.m.) A yearslong attempt to convert a historic Arlington property into a home for adults with developmental disabilities may be nearing the finish line.

The Arlington County Board is expected to consider agreements to transfer the Reeves Farmhouse into the hands of local nonprofits and allocate community development block grant funds later this year, according to a county report. In advance of this, the Board on Saturday took steps toward streamlining the efforts of Habitat for Humanity DC-NOVA, HomeAid National Capital Region and L’Arche of Greater Washington.

Officials voted to approve a use-permit amendment and accept permit applications for building and land disturbance activity — decisions that will make it simpler for nonprofits to renovate the property if they assume possession of it.

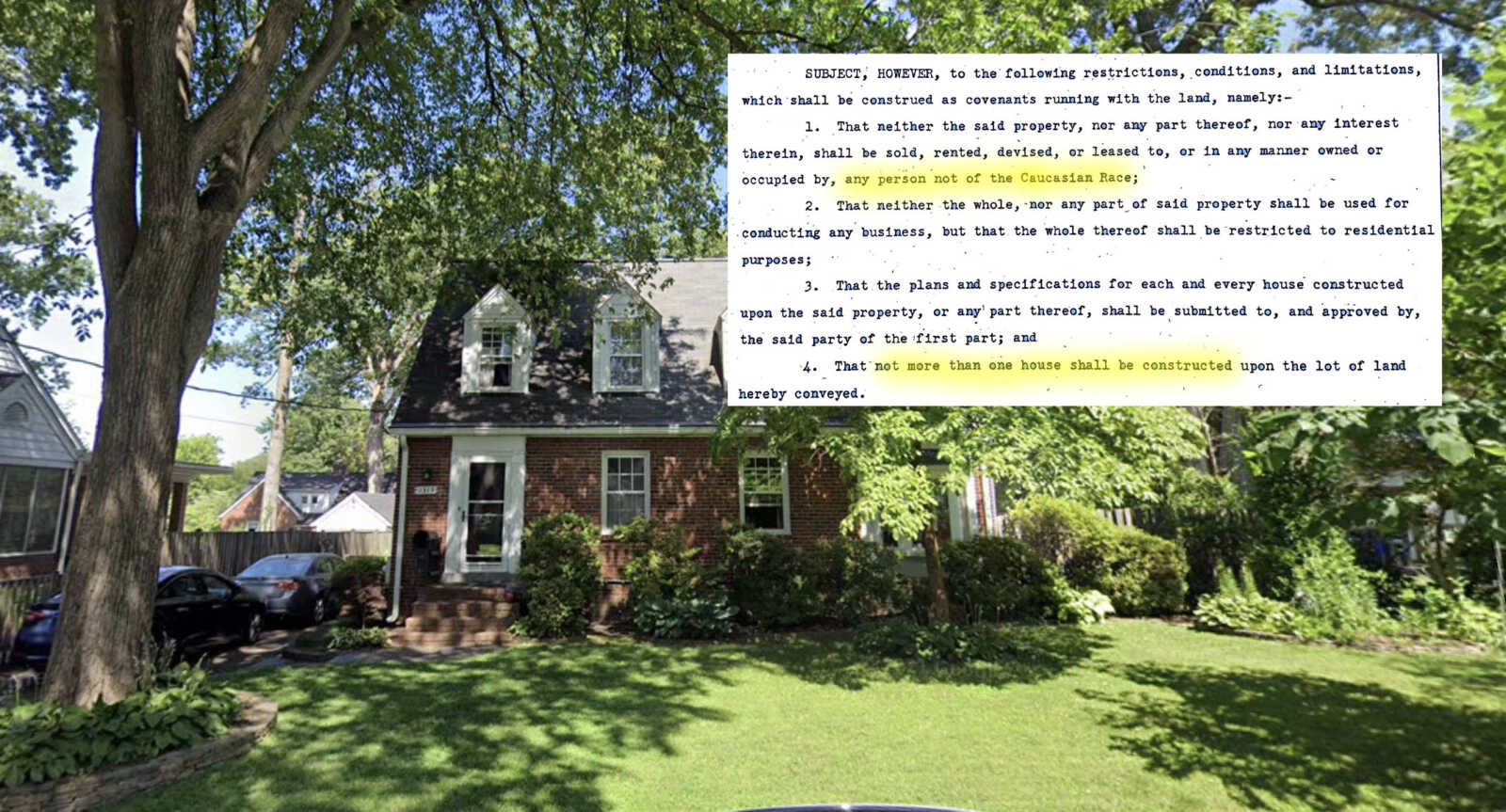

The county report argues that the nonprofits’ plans, which have been refined over extensive conversations with local agencies, are in keeping with the county’s vision for the 124-year-old Boulevard Manor structure.

“As proposed, the historic building will be renovated and expanded in a historically sensitive manner, to provide for the needs of the applicant and the intended residents of the building,” the report says.

Six years of planning and increasingly firm agreement on what to do with the farmhouse led up to this point.

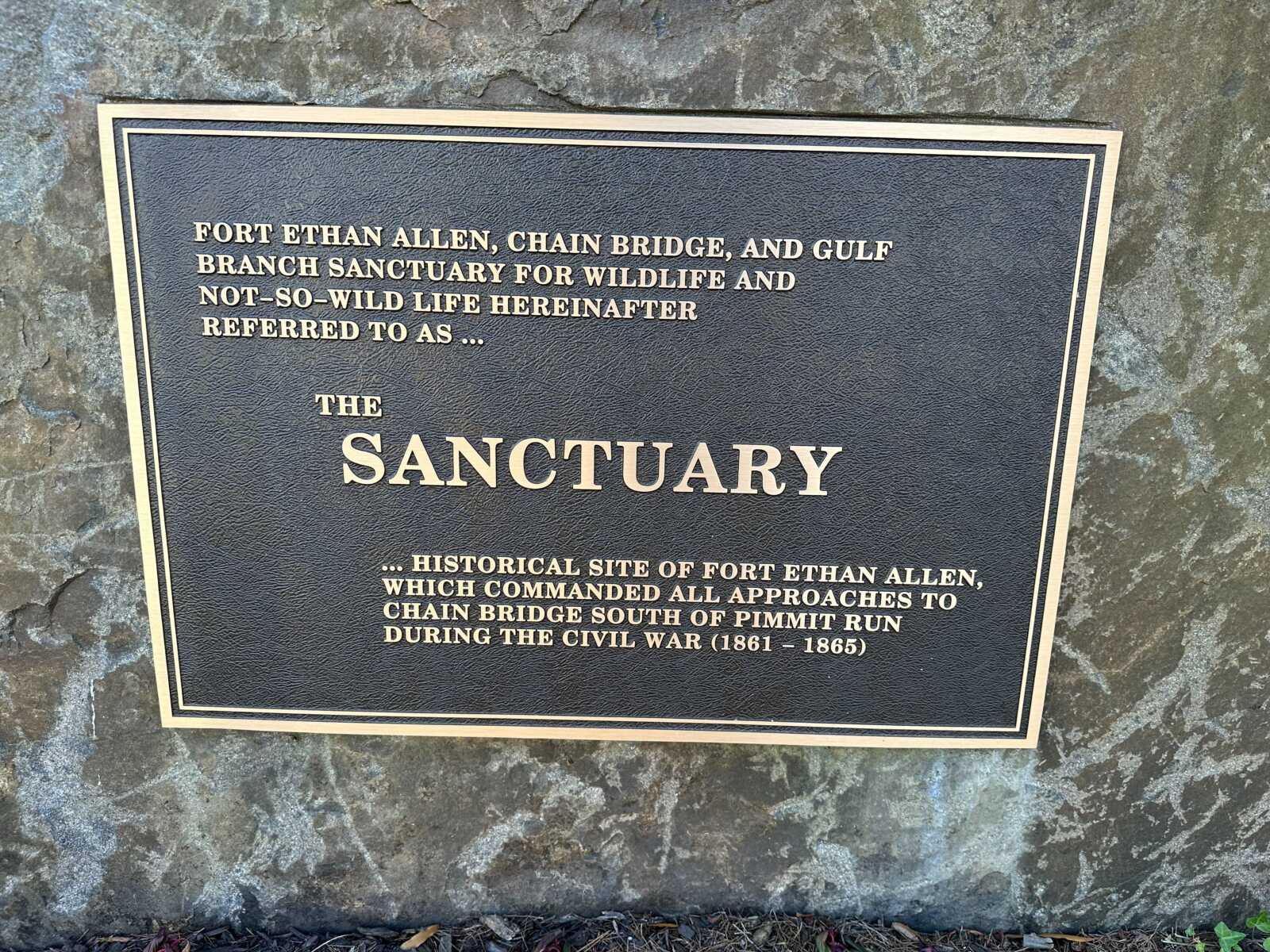

The structure, which was built in 1900, sits on a property that was home to the last remaining dairy farm in Arlington County before it closed in 1955.

The county once considered transforming the farmhouse into a museum or learning center, but ultimately concluded these changes would be too expensive. The county entered talks about transferring possession of the property back in June 2018.

It took three years, but the county and nonprofits finally reached a non-binding letter of intent in February 2020 — just before the pandemic hit.

Talks about what to do with the building stalled for another three years. But they revived in April 2023 when Habitat for Humanity, HomeAid and L’Arche met with the Historical Affairs and Landmark Review Board to discuss the home’s future.

The review board gave its official stamp of approval to proposed renovation plans at a July meeting.

The nonprofit coalition hopes to build a two-story addition on the south side of the farmhouse and a one-story addition on the west side, giving the home a total of seven bedrooms. Housing fewer than eight people, per the county report, means the building would be legally classified as a dwelling and not a group home.

The prospective owners also intend to outfit the existing structure with the following features:

- New exterior guardrails and handrails

- A new front door

- New gutters and rain spouts

- New asphalt shingles

- Two windows in the new shed-roof dormer

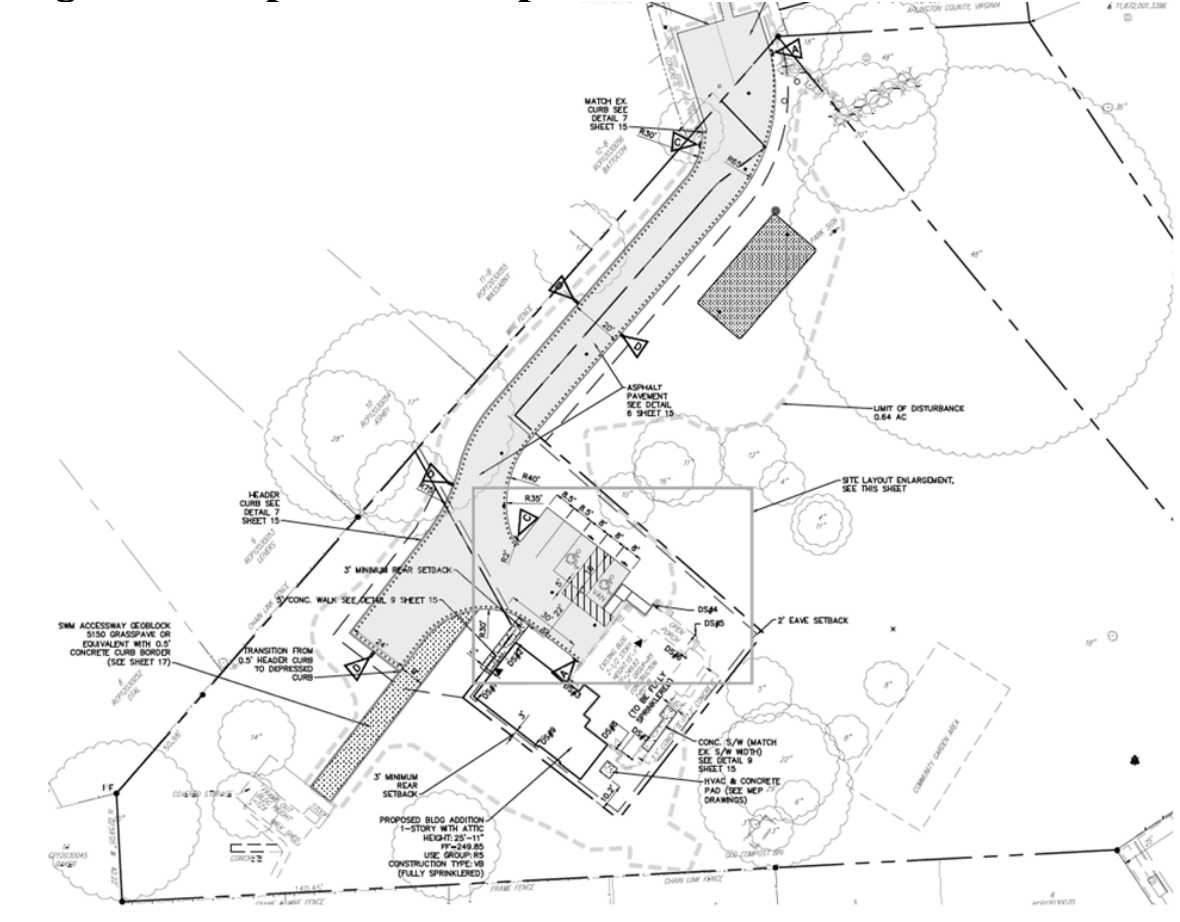

The farmhouse would receive a new driveway allowing for “adequate emergency vehicle access,” along with four parking spaces, two of which would be handicap accessible. Plans additionally include stormwater management facilities and landscaping enhancements.

Other parts of the historic property, including a popular sledding hill — heavily utilized after the recent snowfall — will remain open to the public.

“The sledding hill has been a constant. Everybody wants to make sure we kept that sledding hill,” County Board Chair Libby Garvey said on Saturday.

The Board’s vote makes it possible for Habitat for Humanity, HomeAid and L’Arche to continue pursuing their plans. County staff argued that this decision is in keeping with the goals for the Reeves Farmhouse that the county adopted in 2015.

“Staff believes that the proposed renovations and site improvements to accommodate the applicant’s intention to own, renovate, and operate the Reeves Farmhouse as a residential dwelling providing care for adults with developmental disabilities [continue] to meet these criteria,” the report says.