Demolition began this weekend on the 70-year-old Broyhill mansion in the Donaldson Run neighborhood.

The lengths to which some have gone to oppose it, including allegedly impersonating a photographer and stealing tile today (Monday), has left a bitter taste in the mouths of the owners.

The 10-bedroom home at 2561 N. Vermont, near the Washington Golf and Country Club, went on the market last November for $3.6 million after the previous owner died and the beneficiary, the Catholic Prelature of Opus Dei, decided to sell it to a residential buyer, the Falls Church News-Press reported.

As of January, the only interested buyers were husband-and-wife duo Mustaq Hamza and Amanda Maldonado. They purchased the home — described on Redfin as a “jewel [that] unfolds like a diamond necklace” — f0r more than $1 million under asking price, with the intention of knocking it down and building something more suitable for family life.

“The house was built for entertaining, not for raising a family,” Maldonado told ARLnow this morning.

Some however, are upset to see it go. On Saturday, Hamza said people shouted profanities and walked onto the property and demanded materials be set aside.

“That’s not what we expected when we were trying to plan,” he said, adding that now, he and his wife are doing some “soul-searching.”

“Our intention coming here to build the house for our family seems predicated on the fact that this was a nice neighborhood to raise our children in and stay forever,” he said. “It seems not to be the case, and disappointed as we are, we’re open to having been wrong.”

Unwanted visitors — flouting signs saying “private property” and “danger” — continued on Monday afternoon, when ARLnow photographer Jay Westcott was taking photos of the demolition.

When Westcott arrived, he met a man impersonating a photographer, who announced he was “here to take the pictures.” In addition to a camera, he wore a fluorescent vest, a hard hat and a K95 mask, and left in his red Prius with, Hamza says, historically unremarkable tiles and air filters. He says he is considering filing a police report.

The couple insists that the home is not the historical marvel it has been made out to be. They have preserved items inside and given them away if people requested them, the couple said.

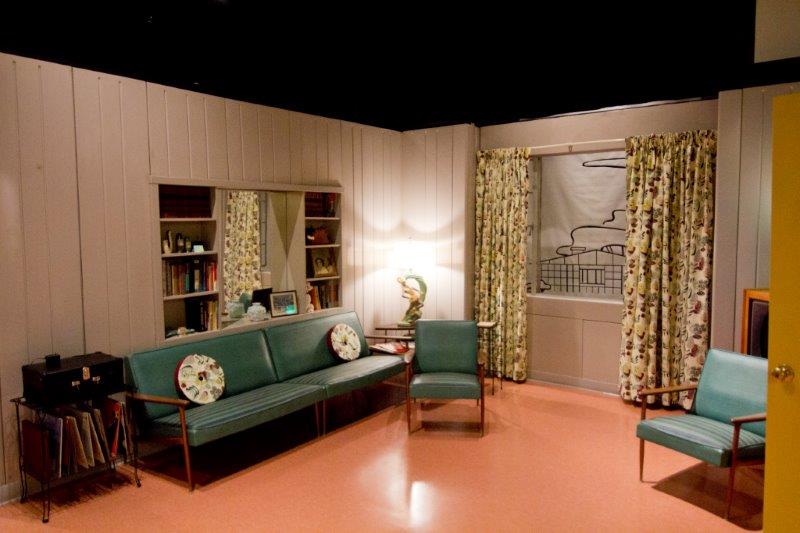

“There’s nothing architecturally stunning about the house — it’s a 1950s replica,” Maldonado said. “There’s nothing in the house that can’t be purchased today. We looked to see if there was anything worth preserving and anything that there was, we saved.”

Northern Virginia home builder Marvin T. Broyhill Sr. built the mansion in 1950 after making his fortune building the classic 3-bedroom brick homes that could be bought for $20,000 during the post-World War II housing boom, according to the neighborhood conservation plan for Donaldson Run.