This weekend the League of Women Voters of Arlington is hosting a workshop to educate residents about the history of racism behind American — and Arlington’s — housing policies.

The free workshop is co-sponsored by the local NAACP branch and the nonprofit Alliance for Housing Solutions, and will run from 1-3 p.m. this Saturday, September 28 at Wakefield High School.

Local nonprofit Challenging Racism will explain how the federal government denied black homebuyers mortgages — a policy known as redlining — and subsidized white suburbs.

Former Wakefield teacher and co-founder of Challenging Racism, Marty Swaim, told ARLnow that the Federal Housing Administration started subsidized mortgages during the Great Depression — but only to whites. In segregated Arlington, this led to developers building suburbs for white buyers who could access the federal program helping them afford the properties.

“It depressed the value of black properties because it made those areas even less desirable,” Swaim said. “It’s a cascade of effects.”

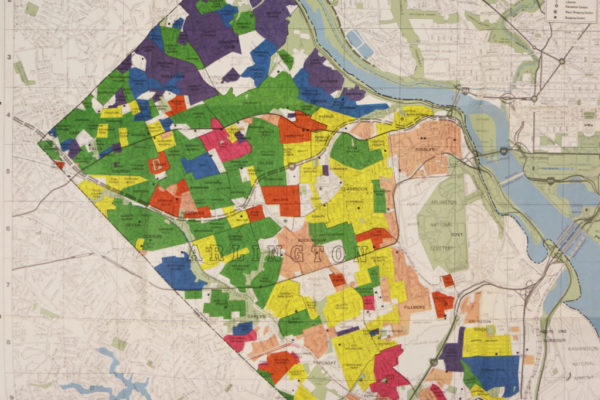

One 1971 HUD guide for homebuyers in Arlington, retrieved from the Center of Local History’s archives, mapped housing by price. Black neighborhoods like Hall’s Hill and Green Valley were color-coded in red to signify the lowest home values (under $20,000.) Whiter neighborhoods in North Arlington were shaded blue and purple to indicate more attractive homes valued between $40,000 and $50,000.

“A lot of Federal Housing Administration loans went to people who settled in these areas, and they were all white,” said Swaim.

Redlining was in addition to another form of discrimination prevalent in Virginia: restrictive covenants on deeds that prevented homeowners from selling to minority homebuyers. Some such covenants remain on deeds in Arlington, unenforceable but a reminder of the state’s segregated past.

Redlining and restrictive covenants were outlawed in 1968 with the passage of the Fair Housing Act, a bill which took years to gain traction. In 1965, activists in Northern Virginia led a petition drive to support it, garnering signatures from 9,926 Arlingtonians, some of whom reporters from the Arlington Sun described as signing the petition in secret from their husbands or neighbors.

“It is abundantly clear that the Negroes will be welcomed in hundreds of neighborhoods in Northern Virginia,” activist Arthur Hughes told the Sun at the time.

But even after the Fair Housing Act passed, decades of discrimination would affect black neighborhoods in Arlington, and nationwide, for years to come.

“Arlington is not immune,” agreed Carol Brooke, who heads the League’s Affordable Housing Committee.

Brooke said Saturday’s event is an opportunity to highlight how racist policies shaped neighborhoods and determined who has been allowed to call Arlington home.