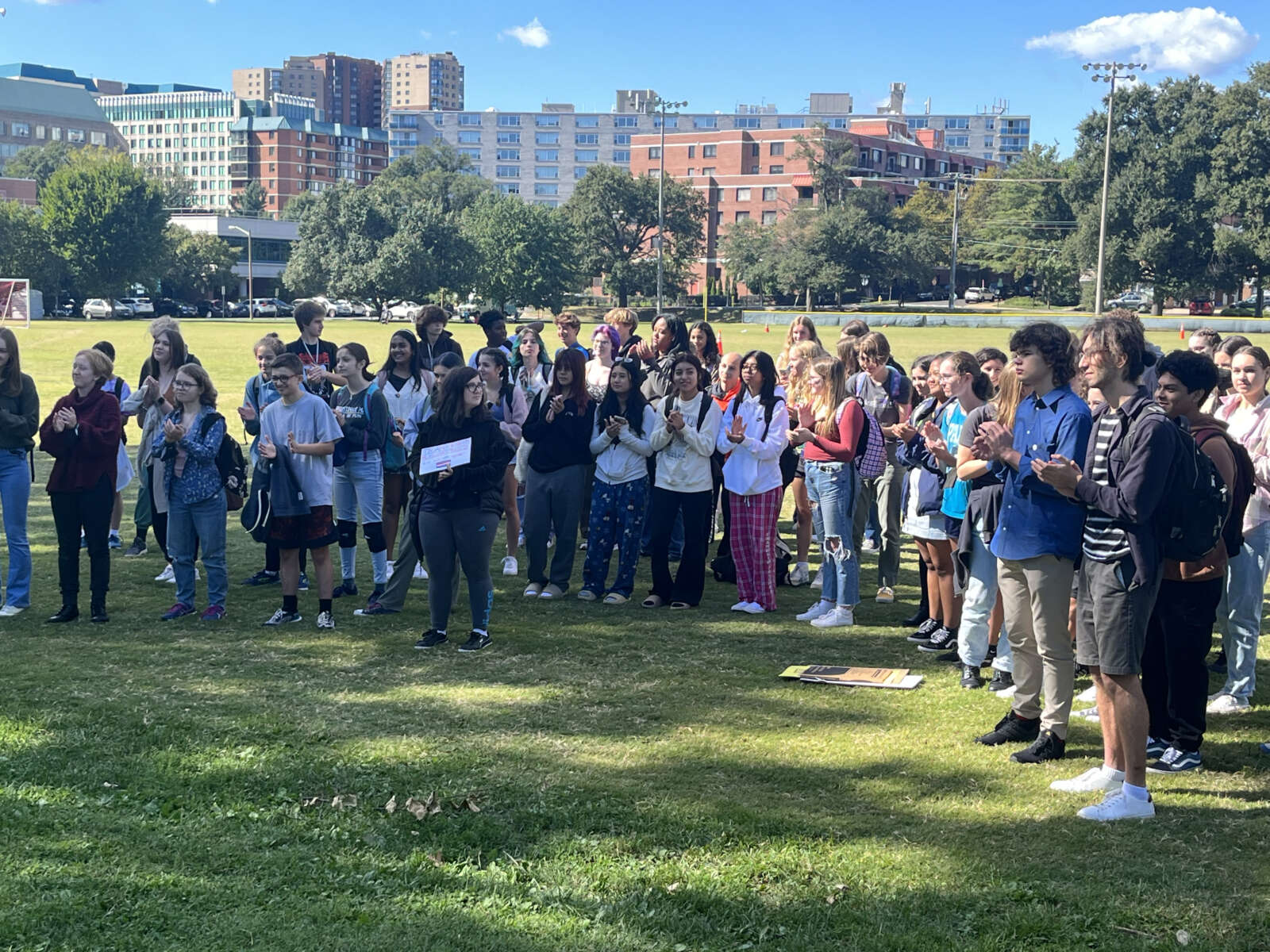

In one year, a group of Washington-Liberty High School students built a subatomic particle detector from scratch, teaching themselves everything from a new coding language to how to solder.

Now, that hardware and software are set to get launched into space this week, though a date has yet to be set.

“I feel ecstatic,” senior Ava Schwarz tells ARLnow.

Their project, originally scheduled to launch on Friday, will help scientists who are researching particle physics understand the kind of atmospheric radiation that rockets experience on flights just under the line between “space” and “outer space,” which is 62 miles above sea level.

Currently, scientists know that there are electron-like particles called “muons” that form when x-rays and gamma rays produced by stars, including the sun, react with particles in the Earth’s atmosphere. Someone even invented a detector to figure out the strength and magnitude of the muons.

What scientists want to know is where exactly these muons get formed — and that is what the students set out to discover. They proposed building detectors and launching them into space to measure the altitude where they are formed and NASA accepted the project.

The team from W-L did so as part of the inaugural NASA TechRise Student Challenge, which was designed to engage and inspire future STEM professionals. The students comprise one of the 57 winning teams to receive $1,500 to build their experiments and receive a NASA-funded spot to test them on suborbital rocket flights operated by Blue Origin or UP Aerospace, per an Arlington Public Schools press release from last year.

The W-L students essentially started from scratch.

“A year ago, I didn’t know what a muon was,” Schwarz said. “I started completely from ground zero and took a crash course in particle physics, electrical engineering — the whole works.”

Senior Pia Wilson was a teammate with, comparatively, substantial coding experience. Suddenly, she was knee-deep in professionally created code using a language she had never worked with before.

“It was definitely a lot of Googling, lot of scouring forum posts in all the coding forums and a lot of help from professionals as well,” she said. Wilson added that she never expected learning how to solder electronics while in high school.

When they needed an expert with whom to talk through a problem, they spoke with associates of their school supervisor, Jeffrey Carpenter — who got into teaching after a 20-year career in space operations — as well as the person who invented a muon detector, Massachusetts Institute of Technology research assistant Spencer Axani.

“It was a very ‘two steps forward, one step back’ process,” Schwarz said. “We were going into a high-level project without a foundational skill set, which we obtained through trial and error.”

Whenever the detector malfunctioned, she said they troubleshooted by eliminating what the problem was not.

“There were many, many afternoons that turned into evenings spent after school, just working for hours, figuratively banging our heads against the wall,” she said.

As the experiment dragged into the summer last year, they kept hitting technical setbacks, particularly with the weight of the detector. They sometimes worried they would not finish in time for launch.